As the first Gulf War was starting 30 years ago, Eastern Air Lines (EAL) took its final breath on January 17, 1991. Eastern’s death was a cautionary tale of the unintended consequences of the deregulation of the airline industry which began in 1978, plus a series of contentious labor/management battles throughout the 1980s which led to its sale to corporate raider Frank Lorenzo’s Texas Air in 1986 and its ultimate demise five years later.

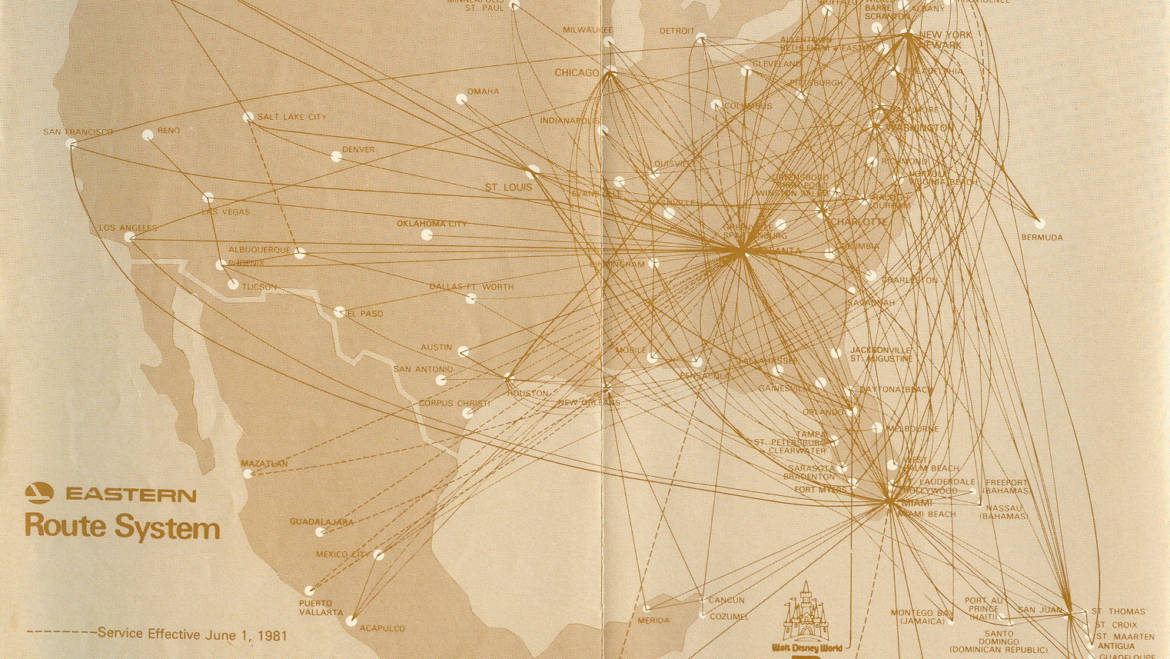

Because so few millennials and no Gen Z ever flew on the “Wings of Man” (from a famous advertising campaign of the 1970s), it’s worth noting Eastern’s rich legacy of innovation (the Eastern Shuttle of the 1960s with hourly flights from BOS-LGA-DCA and EAL serving as The Official Airline of Walt Disney World from 1971-91 are two of many) and celebrity CEOs (from Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, WWI flying ace and CEO from the 1930s to the early 1960s to Colonel Frank Borman, NASA astronaut and CEO from 1975-86). It was the largest airline in the “free world” – only Aeroflot had more planes/flights. Both of my parents worked for EAL: my mother in various Reservations roles in IND, ATL, CLT and MIA from 1960-71, and my father as a flight dispatcher and Systems Control at PHL, JFK and MIA from 1951-88, so I had a front row seat for this corporate Greek tragedy as it unfolded throughout Borman’s tenure – and my childhood and adolescence.

Why on earth in February 2021, as a global pandemic still rages, my children are still in a hybrid school format and my consulting clients ask for competitive intelligence and reputation management best practices for the 2020s, am I going “old-school” to the Reagan Eighties and the end of the Cold War for inspiration? Blame it on a letter to the editor in The Economist from the 2 January print edition from none other than the aforementioned Frank Lorenzo…

“Bartleby summarised a new book by David Bodanis on fairness in business (December 12th). The column narrated the story of Eastern Airlines by describing it as a corporation built by Eddie Rickenbacker, “who had granted mechanics a 40-hour week, profit-related pay and a pension”, but “when Frank Lorenzo took over the company in the 1980s, he cut wages, alienated the staff and pursued a policy of asset-stripping the company. The workers went on strike in protest and Eastern went bankrupt.”

However, Rickenbacker operated during a lush golden era of air travel. The government regulated air fares, and kept them high. Competition was genteel. Then along came the Deregulation Act of 1978, a sea change in the airline industry. New discount airlines sprouted up and airlines added flights to Eastern’s tourist-oriented routes to Florida. Ticket prices plummeted. Yet the unions refused to recognise these new financial realities. By 1986 Eastern Airlines was on the brink of bankruptcy. That’s when Frank Borman, a former astronaut and Eastern’s chief executive, asked me about a sale to my airline group. He told me he’d decided to sell to us because “the unions wouldn’t make the necessary changes.” When we took over, we thought the unions would understand that change had to come, but they continued to fight. In 1989, needing cash to continue operations, we sold the Eastern Shuttle to Donald Trump for $365m. That reality didn’t soften union intransigence; they fought on, so the airline sadly ended up being liquidated with tens of thousands of jobs lost.

Suffice it to say that Lorenzo’s letter stirred up long-forgotten emotions and recollections of how Eastern was perceived completely differently depending on the stakeholder. I almost forgot that Michael Milken (Drexel Burnham’s junk bond impresario that fueled Lorenzo’s Texas Air warchest) and Donald Trump (in the midst of his Lifestyles of The Rich and Famous with Robin Leach TV branding and the brand-new Trump Plaza in midtown Manhattan to his name) were villians – and that by the time the Fortune Most Admired Companies ranking was launched in 1983, Eastern (and fellow Miami HQ once-proud airline Pan Am) was down near the bottom of the airline pack among the hundreds of industry respondents and financiers, well behind Delta, United and American from 1983-86 (from 1987-90, Texas Air was ranked instead of Continental and Eastern separately). From an employee culture standpoint, my late father warned me that International Association of Mechanics (IAM) president Charlie Bryan was willing to play hardball with Borman well beyond where the pilots and flight attendant unions would likely go. Dad said employees like him with more than 25 years of seniority were far less militant to scuttle the company than younger ones who saw the non-unionized success of People Express, New York Air and Piedmont in the 1980s as a cautionary tale that labor would most likely need to break management’s will at Eastern, or resign themselves to relocating from Miami to Dallas (American), Atlanta (Delta), Chicago (United) or Memphis (FedEx) to join one of the winners of the deregulated industry.

Using the nine FMAC attributes used in the 1980s through today as a lens, here’s my take on why Eastern Air Lines lost its mojo and license to operate:

- Service quality: by the time the US DOT launched airline on-time performance ratings in 1988, the writing was already on the wall for EAL, but Eastern was around 70% (middle of the pack), though it was in the top three number of passenger complaints along with Continental and Northwest (now part of Delta). When its popular north-south routes from the Northeast to Florida were flooded with low-cost airlines with “el cheapo” fares starting with People Express in 1980, it had to match those fares to stay in the game, but it cheapened the whole industry narrative as a negative reputation frame of “Greyhounds of the air” took hold with the flying public. It didn’t have enough business travelers to Florida to offset the legions of leisure travelers, and ended up disappointing most stakeholders with average service levels as a result.

- Innovation: this was not the reason EAL went under. In addition to service innovations like introducing the Ionosphere Club at its hubs and making the first purchase of Airbus widebody jets by a major US carrier, Borman and Bryan were able to agree on a two-year cease fire from 1983-85 which included stock incentive programs for all employees (and 4 union seats on EAL’s 19 person board), which academics like future Labor Secretary Robert Reich and business authors like Business Week’s Aaron Bernstein hailed it as a future blueprint of labor/management collaboration (a full decade before United’s much-heralded ESOP plan was launched through a “Fly The Friendly Skies” TV advertising blitz in 1995).

- Global competitiveness: Eastern bought a deep Latin American route network from Braniff in 1982 for only $11 million, and was able to create a strong brand throughout the region for the remainder of the decade (despite the company’s domestic turmoil). It also inherited the lucrative Miami-London route in 1985 after Air Florida fled for bankruptcy the year before. Its Mexico and Caribbean flights were always sold out for decades, so while EAL was no Pan Am (or TWA to Europe), this was not the airline’s Achilles heel.

- People management: even though Borman was a devout Republican (having served as Nixon’s goodwill ambassador to the USSR following Apollo 8), President Reagan’s anti-labor stance (personified by his breaking the air traffic control union in 1981) was really the kiss of death for the only member of the original Big Four regulated national carriers (TWA, United and American were the other three) that never enjoyed relative labor peace during the regulated era. Organized labor really felt like Eastern was a line in the sand for the movement nationally, and that created a “lose-lose” scenario for Borman, whose debt levels from modernizing the EAL fleet (with major Airbus A-300 and Boeing 757 purchases) in the early days of deregulation gave him little wiggle room by 1985.

- Use of corporate assets: though Lorenzo disputed this in his Economist letter, even my teenage reading of the Miami Herald, New York Times and my dad’s copy of Aviation Week & Space Technology made this the smoking gun proving Eastern’s corporate reputation guilt with most stakeholders – from Wall Street (those who were turning against Drexel Burnham and the rising tide of junk bonds) to Main Street, especially among travel agents who were the primary gateway for airline ticket purchases from the 1950s through the rise of the Internet a decade later. Bernstein chronicles the “Texas Air Chainsaw Massacre of Eastern Air Lines” in chapter five of his excellent 1990 book Grounded: the sale of Eastern’s computerized reservations system (SODA) connecting 5,000 travel agents for only 40% of its value, valuable airport gates and commuter airline stakes for a pittance, and eventually the Eastern Shuttle to Donald Trump in 1989 for $365 million. Amazingly, Lorenzo agreed to pay $280 million in a settlement out of court in March 1990 about Texas Air’s asset-stripping of Eastern Air Lines, which only served as a moral victory for Lorenzo’s union opponents and came much too late to save Eastern’s 40,000 employees their jobs. Eastern wasn’t Enron or WorldCom from a decade and a half later, but Lorenzo’s financial engineering gone bad was a clear reputation red herring for Eastern.

- Social responsibility: this was the Reagan Eighties, not the triple bottom line of European CSR fame of decades to come, so no US airline was spending too much time or effort on social responsibility. Anecdotally, my Eastern childhood saw community investments as part of Eastern’s sponsorship of the Doral Open PGA event in Miami (another link to Donald Trump’s future business empire), and my parents’ EAL friends in Atlanta got involved with Habitat for Humanity from its inception in 1976. But this was not a major reputation driver for EAL with any contemporary stakeholders.

- Quality of management: I still give Borman a great deal of credit for how he navigated Eastern’s entrance into the wild world of airline deregulation from 1975-85. He bet the ranch on fuel efficiency to leapfrog the newer fleets of American and United in the late 1970s, and his A-300 and B-757 purchases would have been genius IF the fuel markets of the 1980s behaved more like the 1970s. With oil prices cratering from 1980 ($37/bbl) to 1986 ($15/bbl), it made EAL’s high fixed labor costs the only lever that Borman could wield to try and gain competitive advantage, and it became the hill the Colonel died on, and the grenade that Lorenzo detonated during Texas Air’s infamous ownership. In the end, the celebrity CEO giveth and taketh away from a company’s reputation, and Apollo 8 might as well have been the Roman Empire to Charlie Bryan and the IAM when they smelled blood in the water in 1986 and pushed Borman to sell.

- Financial soundness: with annual revenues exceeding $4 billion by the mid-1980s, Borman was able to have eight consecutive quarters of profitable growth from 1983-85 during the brief ceasefire in the management/labor wars that came before and after. If a buyer who was interested in rebuilding Eastern as a future industry leader had been found instead of a corporate raider, who knows what might have been. In fact, this story could have had a Hollywood ending, as Peter Ueberroth (former baseball commissioner and hero of the 1984 Summer Olympics in LA) emerged as a “white knight” to liberate EAL from Lorenzo in 1989 before talks fizzled out. Instead, the world got the Trump Shuttle for a few years before it shut its doors too, and sixty-five years of aviation history down the drain.

- Long-term investment value: in the deregulated airline industry, shareholder value was unpredictable and past performance was no indicator of future success. Case in point: after Borman’s labor peace deal with the unions in 1983, EAL traded at 11 3/4 (pre-decimal points on the NYSE!), but by January 1985, it sank as low as 3 1/2, before doubling to 7 5/8 by April. This was the golden age of corporate raiders – Carl Icahn nabbed TWA in 1985, and Lorenzo started out with tiny Texas International in the early 1970s but then gobbled up quite a list of once-proud fleets during the 1980s: Continental, People Express, New York Air, Frontier and Eastern. Their mantra – buy low, sell high, which was good for a small subset of investors but bad for the American public who saw the democratization of the skies with deregulation ruin many employee careers and taint domestic air travel which had been perceived as jet-setting and glamourous just a generation earlier.

At the end of the day, Eastern Air Lines was a flawed organization where management hubris (Rickenbacker was a late adopter of jets, and Borman felt like he could charm the union leaders until the very end – especially the pilots) and union militancy (Bryan was the wrong man at the wrong place at the wrong time – think of Charlie as the anti-Walter Reuther of the UAW during post-war Detroit’s automotive management/labor renaissance) mutually assured the destruction of a once-proud airline. When you foul up people management, use of corporate assets and financial soundness as EAL did pretty spectacularly on its own and then as part of Texas Air during the 1980s, it’s damn near impossible to earn enough trust, admiration and goodwill to stay afloat.

In future posts, I will look at Eastern’s legacy more specifically from different stakeholder perspectives as I come to grips with nearly a half-century of Patterson family history as a 2021 passion project. I would love to hear from my LinkedIn network about your Eastern experiences – and in the meantime, I want to thank Frank Lorenzo for his letter to the editor that lit the spark in uncovering Eastern’s reputational fall from grace during the first decade of airline deregulation!